Labor Day marks the end of summer, going back to classes, and the end of being able to wear white until next year. But, what even is Labor Day? According to the US Department of Labor, the first Labor Day occurred on September 5, 1882 in New York City and was organized by the Central Labor Union. In 1884, the first Monday in September was selected as the holiday’s official date. Central Labor Union urged similar organizations in other cities to also participate in celebrating the “working men’s holiday.” By 1885, Labor Daywas celebrated in many industrial centers across the country. The purpose of the holiday is to honor workers who often go unappreciated in everyday society.

So, what do women have to do with “working men’s day?” Actually, quite a lot. From the beginning, women have played a major role in the labor movement, although they rarely receive proper credit or appreciation. According to Shmoop, women were amongst the first workers to start unionizing. Young women were hired to tend power looms in New England’s factories towards the start of the industrial revolution, making them some of the first workers exposed to the dangers of the industrial workplace. In the 1830s, women working in textile mills in Lowell, Massachusetts began to protest their poor working conditions and low wages. This gained them national attention in 1834, when their pay cuts lead them to walk out and strike. By 1846 this turned into the Lowell Female Labor Reform Association, which lobbied for 10-hour work days—that sounds like a long day now, but was a big improvement from their usual 14-hour days. The movement was not limited to white women in New England factories, though. In 1886, newly-freed black women in Jackson, Mississippi formed a union and went on strike to demand higher wages for their work at laundresses, according to United Healthcare Workers West’s timeline of women’s contributions to the labor movement.

But even

But even

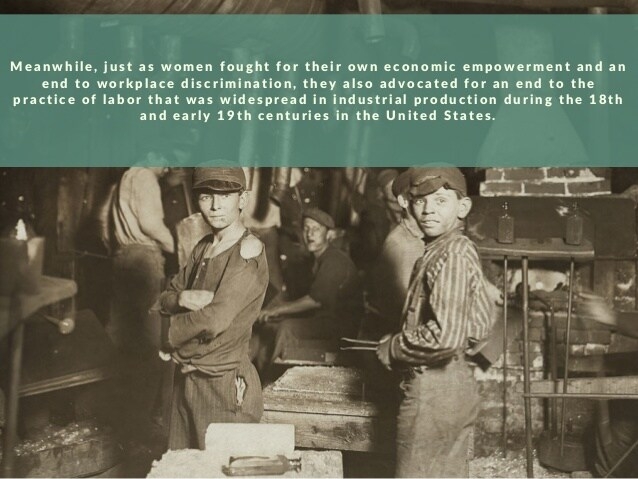

though women had been contributing to the movement for 50 years, in 1886, the American Federation of Labor (AFL) was founded and its first president, Samuel Gompers, denied membership to women. It wasn’t until 1903 that the Women’s Trade Union League was formed at an AFL convention, which was the first national association for organizing working women. That same year, Mary Harris Jones, a notable organizer nicknamed “Mother Jones,” lead a 125-mile march of child workers to expose the child abuse that occurred in factories.

In

In

1912, immigrant women left their mark on the movement by organizing the Bread and Roses strike, which brought 23,000 men, women, and children on strike with 20,000 of them on the picket line. That same year, Massachusetts established the first minimum wage law, which extended to women and children. It was also the year the Department of Labor was born, although it was not until 1920 that it added the Women’s Bureau. In 1933, President Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed Frances Perkins as the first female cabinet member to be the Secretary of Labor. She served a paramount role in helping to create Social Security and the New Deal. The saying goes “behind every great man there’s a great woman,” which is offensive but true, and Perkins became just that to FDR. Although the Women’s Pay Act of 1945 was the first legislation that would have required equal pay, equal pay was not passed until 1963 when FDR included it in part of his New Frontier Program. Thought FDR recieves the credit, it was probably also due in part to Perkins' influence.

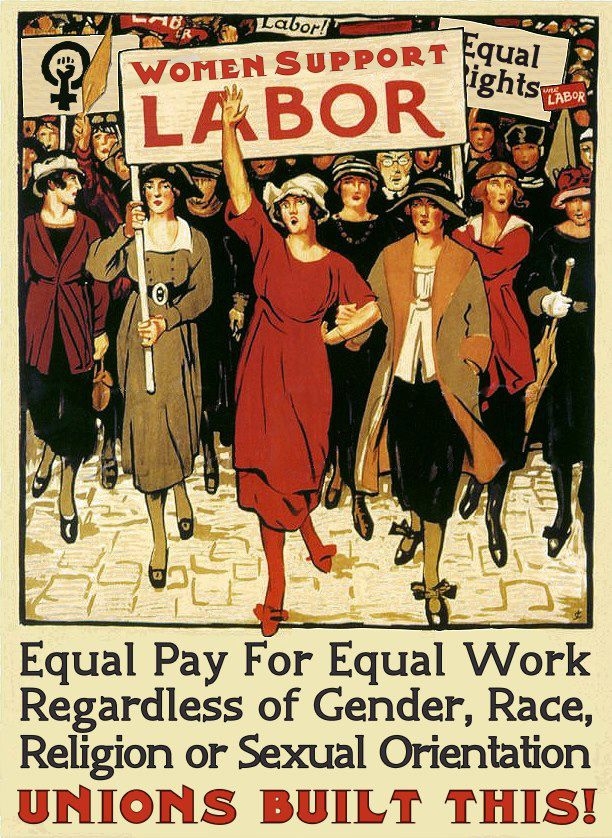

Even after all of the work women put into the movement, we still have a way to go. As of 2016, women make up 47% of the labor force and are the sole or primary breadwinners for 40% of families with children, according to the Shriver Center. Almost every occupation has a wage gap which affects women, and women of color the most. According to National Women’s Law Center, two-thirds of low wage workers are women, and nearly half of low wage workers are women of color. Domestic work, such as nannying, housekeeping, and providing homecare, is done by women 95% of the time. This "women's work" lacks the employment protections that other industries have, leaving workers unprotected by the laws for minimum wage, time off, sexual harassment, and the right to unionize. Those lack of protections lead to domestic work being a significant industry for labor trafficking, according to the Shriver Center. In industries where women have become well integrated, they still remain at the bottom of the pay scale. And as we have seen with the #MeToo movement, women are at risk of facing discrimination and harassment at work, which leads to further mental and physical harm. So go have a fun day at the beach—but don't forget all of the women, past and present, who dedicate their lives to a better life for all of us.